Primary Source Set

by Greta Bahnemann, Metadata Librarian, Minnesota Digital Library, Minitex

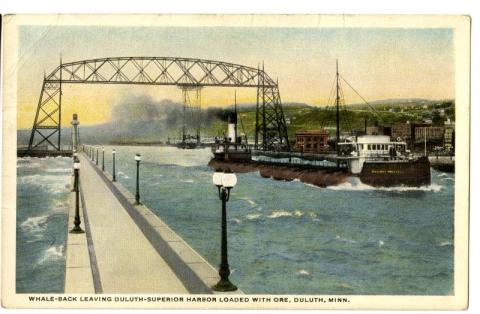

Whaleback Boats count as just one of the many stories unique to the Great Lakes. Duluth’s Captain Alexander McDougall was an experienced Great Lakes seaman and ship’s master. He conceived of this unique form of transportation in 1888; and by 1970 the last whaleback was retired from service. Although their time of active service was less than a 100 years, whaleback boats made a lasting contribution to the maritime history of the Great Lakes.

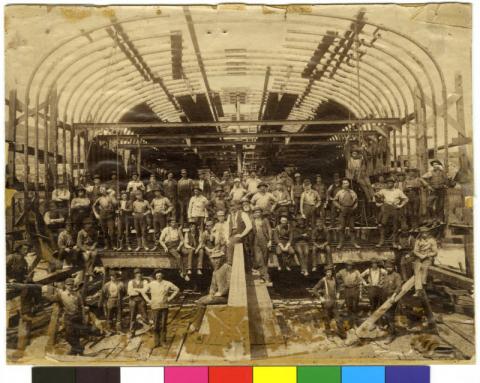

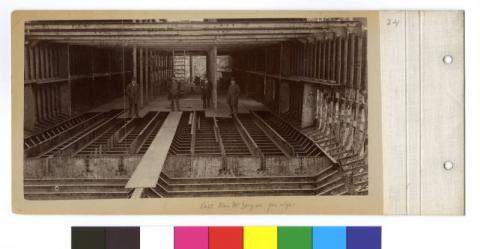

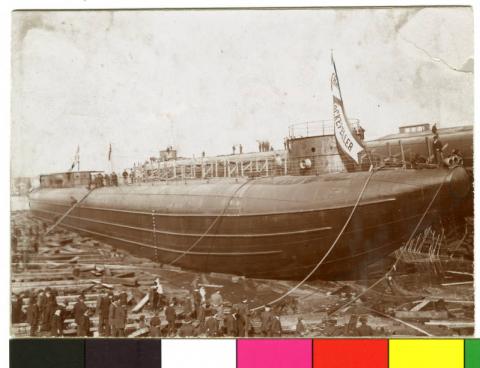

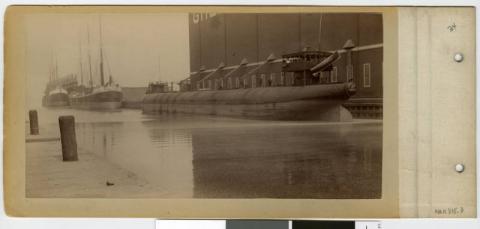

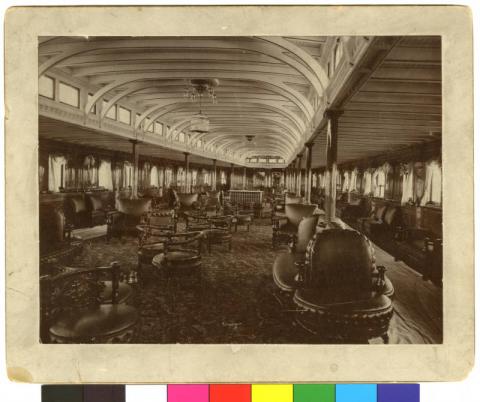

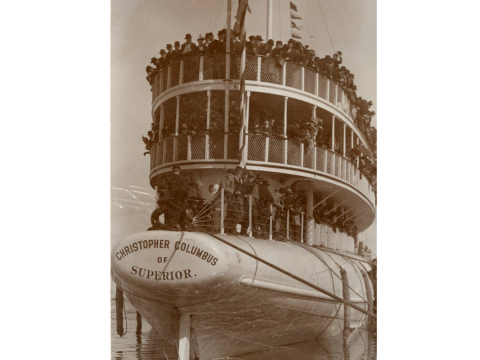

What is a whaleback boat exactly? McDougall designed whaleback boats to serve as seaworthy freight haulers. These cargo steamships hauled bulk freight, such as grain, gravel, and iron ore. McDougall believed that his boats could efficiently haul the iron ore from the ports of western Lake Superior to points east. The boat’s continuously curved hull created a profile in the water that lead to their name. With a cigar shaped body, a fully loaded boat looked something like a whale in the water. The designer placed both pilothouse and cabin above the waterline. The first whaleback boat was constructed in Duluth, Minnesota in 1888 and was christened “McDougall’s Dream.” Subsequent boats were built across Superior Bay at a boatyard in Superior Wisconsin.

Alexander McDougall’s dream was not without its problems. A design flaw greatly limited the whalebacks ability to haul iron ore. The hatches on the boats were smaller due to the curved hull. The smaller hatch size meant to slower loading and unloading times. This led to several innovative solutions, including converting some of the whalebacks to self-unloaders and changing the freight the boats hauled to grain, sand, and fuel. The whalebacks were also vulnerable to storms and collisions with other boats due to their low profile on the water. Reports of the time recount accidents in which others boats literally ran over the bow of a whaleback boat.

Perhaps the most famous whaleback was the “Christopher Columbus” which was designed as a passenger shuttle for the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago (also referred to as the Chicago World’s Fair and the Chicago Columbian Exposition). This whaleback had multiple levels for passengers and ferried more than 2 million people to the fair’s site during the fair’s 6-month run.

The “Meteor,” the last whaleback in active service, ran aground near Gull Island on Lake Superior in 1969. Due to severe hull damage, the owners chose not to repair the 73-year old steamer; but rather the ship was eventually donated to the city of Superior, Wisconsin where it is now a museum ship.

Discussion Questions & Activities

1. How difficult would it be to develop an entirely new kind of boat? What would be the steps involved in developing this new boat? What considerations would you need to make in the boat's design? What might prompt you to design an entirely new type of boat?

2. Can you think of other examples of inventions that came and went very quickly? (Hint: zeppelins filled with hydrogen gas and others). What factors determine the success of a new invention?

3. Do you think different kinds of freight (iron ore, lumber, grain, etc.) change or impact the design of lake freight haulers?

4. Do changes in the demand for goods and products necessitate changes in transportation?

5. What are some other examples of animal forms and animal functionality used in modern design?

6. Design a boat and plan for where the boat will be used, what it will be hauling, and whether it can also transport passengers. What are the advantages of your boat? What can your boat do that others can't?

eLibrary Minnesota Resources (for Minnesota residents)

1. "Great Lakes." Britannica Academic, Encyclopædia Britannica, 22 Dec. 2008. Accessed 12 July 2017.

2. Jackson, Matt. "Dangerous Waters." Beaver, vol. 84, no. 3, Jun/Jul2004, pp. 36-39. Academic Search Premier, EBSCOhost, Accessed 12 July 2017.

3. "Superior." Britannica School, Encyclopædia Britannica, 2 Sep. 2011. school.eb.com.proxy.elm4you.org/levels/high/article/Superior/70395. Accessed 17 Jul. 2017.

Additional Resources for Research

1. Mixter, Ric. "McDougall's Dream." Michicagn History Magazine, volume 97, no. 3, May/June 2013. http://www.hsmichigan.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/McDougall. Access 12 July 2017.

2. Oakley, Janet. History Link.org "Whaleback Freighter Charles W. Wetmore arrives in Everett on December 21, 1891." http://www.historylink.org/File/7362. Accessed 7 July 2017.

3. Wilson, Thomas. Minnesota Historical Society. "Lake Superior Shipwrecks: Whaleback Freighters." http://www.mnhs.org/places/nationalregister/shipwrecks/wilson/wilwf.php. Accessed 7 July 2017.

Published onLast Updated on